Due to the overwhelming popularity (silence) of my blog, a good friend asked me to reproduce this essay on the Great Gilda

Gilda Cordero Fernando as Life Coach

by Elizabeth Lolarga

Gilda Cordero Fernando. The Last Full Moon: Lessons on my Life. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press and GCF Books. 2005. 250pp.

Sylvia Mendez Ventura. A Literary Journey with Gilda Cordero Fernando. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press. 2005. 174pp.

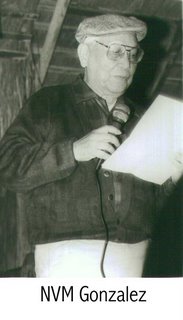

Was he being cantankerous or issuing a left-handed compliment when the Grand Ole Man of Letters Nick Joaquin once said of Gilda Cordero Fernando: "We have no other writer capable of such sublime nonsense?"

We have reason to object for the woman is far from flighty, superficial and wispy. Talk of woman of substance, of Mother Earth and sexy septuagenarian all in one! Every writer, male or female, looks up to her for her accomplishments as fictionist, essayist, editor, publisher, theater producer, fashionista, art patron, painter and what her best pal Mariel Francisco describes as "national cultural visionary…an outstanding voice in the expression of the evolving Filipino world view."

Heck! Fernando should've been named National Artist for Literature (or even Multi-media if the authorities ever put up such a category) years ago if not for the corrosive power struggles that mark the, ahem, sublime world of arts and culture.

Now in the autumn of her life, still garbed in avant-garde threads sewn by who's ever hot in the couture world, seen by literary scholar and friend Ventura as "keep(ing) old age at bay by moisturizing her unblemished skin, exorcising the demons of arthritis, hanging out with young adults, and, above all, keeping passion alive," Fernando, 75 this year, gifts us with a compendium of life lessons earned the hard, soul-cleaning way.

Critic Ventura zeroes in on the three central themes that inform Fernando's creative non-fiction (including Ladies' Lunch and Other Ways to Wholeness and A Spiritual Pillow Book, jointly authored, by the way, with Francisco): "her hostility toward her mother, her unequivocal love for her father, and the bewildering state of her marriage."

Not too long ago, writer Bobbie Malay said she still had to read a Filipino woman writer deal honestly with her relationship with her mother, raw emotions and all, not sweetness and light, the way the Frenchwoman Simone de Beauvoir did with her mother. Not too long after that, along came Fernando, and in this she breaks new ground for hasn't Francisco called her an "active door opener," a synonym for trailblazer?

In the third chapter of her memoirs , "The Soap Opera," Fernando uses a no-holds-barred language to describe a violent quarrel between her parents where she witnesses "my father standing on the stair landing, the top of his silk pajamas in shreds and my mother trying to claw off the trousers. Through a big tear on a pants leg, a bit of his penis was showing."

As an only child for 13 years before her sister Tess was born in the wartime, Fernando saw her Mama's upheavals, the hurling of things on the floor at the height of unreasonable anger. Once she threw a bottle of Mercurochrome and a splinter lodged in her daughter's wrist. To this day Fernando bears the scar.

During those pre-Bantay Bata years, the young Gilda, who was spanked with a slipper and almost strangled (with no intention to kill though), was pained to see how the outbursts, quick though they may have been to dissipate, hurt and annoyed those who heard the terrible words. No dirty word though, the author would grant her mother that. When the girl entered her teens, the mother guarded her more fiercely. "She made me guilty, like I were some lascivious child who would run off with the first guy I met."

The worst was the effect on the child's self-esteem. "My mother," Fernando writes, "made me feel that I was the worst person that ever got seeded on this earth…After a while, no matter how hard she beat her devil child, I didn't feel anything. That's why I understand it when the political prisoners say that beatings don't hurt anymore after a while. You get immune."

In her adulthood, Fernando confronted her aged mother about those beatings, and the woman denied everything. The author rues, "It was as if the God upstairs had given me a mother with so many gifts and talents and said, But you're not about to get them for free! You have to learn every lesson laid before you."

As her maturity deepened along with her well of compassion, Fernando realizes that her Mama, who lost her own mother at age five, also had a self-esteem problem to the point that she thought Gilda "wasn't a good-looking baby. It took a while to convince her that I looked fine…My mother's low self-esteem couldn't convince her that she deserved a pretty child." Fernando adds sympathetically, "But how could I blame her for faulty parenting when she barely had a mama herself?"

Fernando hauls out her honed skills in food description in recreating the dishes that came from her mother's kitchen, a strong point of this older woman with whom Gilda had a lifelong battle. "She liked serving fancy stuff—an incomparable lengua, a capon stuffed with sotanghon and chestnuts, a big fish bathed in mayonnaise and garnished with separate bands of minced carrots, hard-boiled eggs, and sugar beets…Sometimes there was wintermelon soup which was rich chicken broth in a big oiled kundol which stood on its end in a magnificent bowl."

Ventura notes that Fernando's "food essays transcend the usual articles on gourmet feasts served in gated subdivisions and patrician restaurants; they also portray the lifeways of the common folk, their beliefs, superstitions, customs, and culinary procedures which may be old-fashioned but pleasing enough to the palate." (See Philippine Food and Life as an example. Fernando considers it her "best book.")

The critic asks Fernando "if she every drools while writing her essays on succulent food, and her answer is 'Never, pagod na pagod ako.' But her exhaustion never betrays itself, so smooth and effortless is her style."

Back to Consuelo Luna Cordero, Fernando's mother whose influence is far-reaching in her sense of style and grooming. There is a precious chapter on "Mother's beauty secrets that I learned (and unlearned)" wherein the young Gilda is dolled up in Shirley Temple minis that had her pulling down the hem of her dress to hide her panties.

All the way to her 70s when she was producing the theater extravaganza Luna: An Aswang Romance, Fernando still had an axe to grind against her mother. "Not coincidentally," she writes, "my mother's family name is Luna. To me the aswang in the play represents all the things I had not liked about my mother. We were forever quarreling. She had lots of energy which I felt she drew from anger and nervousness. It was like aswang energy. She did not draw from a higher source and her unbridled nervous energy consumed her as it almost consumed me…My black chick was obviously the residual resentment against my mother."

As the production drew close to its premiere, Fernando, in the privacy of her home, dances and flings her arms to the moon, saying, "Mother, forgive me." At 70 she realizes that she also had her share of blame in their "sorry relationship. I had always felt that she was the older one, the parent, and should know better…But now the tables were turned. I realized that even in her intransigence my mother, too, had suffered. And for the first time in my life I felt free of any baggage!" The reader identifies with the closure finally reached.

As for being the apple of her father's eye, Fernando has nothing but good memories of Dr. Narciso Cordero who helped her with her arithmetic and later her algebra, geomety, physics and trigonometry, who read the entire Les Miserables by Victor Hugo while she had a bout of flu, who taught her how to bike during the Japanese Occupation when there was no gas, who softly played a makeshift flute-recorder as she drifted to sleep.

The writer observes how opposite as night and day her parents were: "A cautious man, my daddy descended the stairs on cat feet, one step at a time, holding on to the banister; mama nimbly negotiated the stairs in high-heeled shoes. My father saved money; my mother spent it. He was an indefatigable string-saver, pencil-stub hoarder and soap-paster; my mother blew the money saved on fondue casseroles and imported pink and blue cigarettes…My mother liked to cook; my father disliked to eat. If papa could take his food intravenously, he would be a much happier man."

This is Fernando at her best talking, not hiding behind the screen of fiction. As Ventura notes, "Gilda made a smart decision when she chose to give up fiction for creative non-fiction in the hope that she would attract a wider audience. Her readership expanded, indeed, and she harvested more prestigious awards than she did for her short stories….The fiction-writing instinct has, however, remained embedded in her psyche and has added sparkle to her essays."

Ventura describes Fernando's style as fusing "the methods of traditional exposition (facts, truths, theories) with the forms of creative non-fiction (narration, description, figurative language) in a style marked by vigor, color, and grace."

For choosing writing as her main line, Fernando is grateful to a wartime teacher, a Maryknoll nun stationed in Malabon where Gilda's family fled. She writes, "In every person's life there is someone, usually a teacher, who blazes a path to one's professional life. Sister Maria del Rey did that for me. She had been a Pittsburgh reporter before she became a nun and could certainly practice what she preached. She taught us how to observe things around us and how to describe them in great detail in writing."

While their class was required to write daily themes, by the end of the schoolyear, it was only the young Gilda who persisted on writing till the task "had become a loving, one-to-one tutorial between Sister del Rey and me."

The other person with a lifelong, still continuing influence on Fernando's life is her choice of a mate, Marcelo, whom she described in his youth as "unobstrusive…refined and sophisticated. I was impressed that he subscribed to the New Yorker magazine whose articles I adored. He was intelligent though not particularly sociable, a strong silent type with some mysterious underground current." But most of all she liked the fact that "he never made me feel insecure. I knew that he would take care of me forever and ever."

Although the chemistry that drew them was electric (pun intended; Marcelo Fernando rose to become a corporate executive at Meralco), the marriage went through decades of strife and adjustments. Fernando quips, "Some friends claimed that their marriages were made in heaven; ours seemed more like it was made in a barbecue pit."

One of the sore points that Fernando saw was her husband "both liked my being a writer and hated it because it was the star on top of the litany of interests that we did not share." Furthermore, "more than any man, woman, or child, my husband considered my writing his rival. And maybe so, because it was my passion. I could pour into a piece of paper all my anguish, my fantasies, and my secret desires. I could create a dwelling place, a holy of holies that no one could enter."

The modus vivendi they arrive at is: "I would attend all his Meralco parties and all the birthdays of his relatives but he would never go to any of mine. And he promised to keep supporting me in style all my life. I kinda felt shortchanged there but then how could you win, he's a lawyer."

Any writer, especially a perennially insolvent one, would agree wholeheartedly to such terms. They remain the secret of the couple's more than 50 years of togetherness. "If we shut a door between us, it was only a physical door, to create the space within that is the real sustenance."

In "Private Spaces," Fernando elucidates this idea further. After years of trying to create her own physical space away from the husband's snoring, nighttime reading lamp and TV watching, she finds that she can "create a room of your own within. Meditation could create that space. So could solitary biking, or running, or swimming, or slow dancing, or playing the piano, or painting, or being absorbed in work you love."

She hints on how she learns to forgive Marcelo's indiscretions and "I found I had landed at home. I finally accepted my partner's love the way it was, and had always been, warts and all, with no conditions, realizing at last that the only private space is being at peace with yourself and the one you love."

She once asked her husband what in their life he liked the most. His answer: "That we learned not to get in each other's way." In poetic terms it means: "Giving each other lots of room to grow." The formula works, whether with heterosexual couples wedded in the 1950s like the Fernandos or homosexual pairings in this era.

The essay "Welcome to the grace years" provides other pointers for couples who think their partnerships are falling apart. In one of her epiphanies, Fernando enters her husband's room to find why she had loved him all these years. "…(O)n the shelves were all shapes and sizes of tapes, batteries, scissors, glue, stacks of coin, strings, magnets, clips, pencils, ballpens, post-it, envelopes…I could rely on him—not just for pens and things—but for everything! Advice on an investment, a trip, a gift, the right word, the right wine, the name of a foreign dish…He grounded me and I felt safe with him. He was my Rock of Gibraltar. Never mind if rocks don't fly or kiss and aren't so sociable. Providing is caring, it is love, and how often that is taken for granted."

In "All about happiness," Fernando hazards a scenario where she and Marcelo are always together "maybe in the next lifetime…But for now let him be just him, and me, me. Twin hearts only when we choose to be." Truly a fairy tale for the millennium.

Ventura's conclusion is Fernando is able to "make senior citizenship look and sound funny. As funny as the weird women in her paintings, swathed in wild colors, frizzy hair askew, pouting, grimacing, pursing their lips, piercing you with witchy eyes, gazing tenderly at a crescent moon."

Columnist Alfred A. Yuson's gripe over Fernando's book is that it sounds like "a sort of swan song, ironically enough from the Grace Kelly of Philippine literature." On hearing of this, Fernando, holding a glass of red wine, shook her head and laughed , "But Grace Kelly is the Ice Queen. I'm the hotsie patootsie of my generation!"--First published in Ti Similla, academic newsletter of the University of the Philippines Baguio