Basketball Madness Part 1

From Boston Globe's The Art of Sports

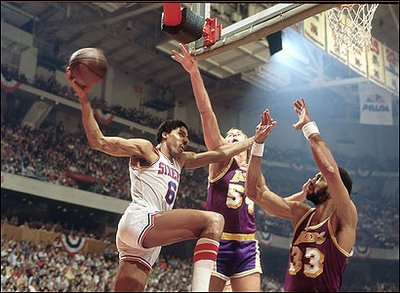

The art critic Dave Hickey builds his essay ''The Heresy of Zone Defense" (published in his 1997 collection ''Air Guitar") around another such moment of transcendent athletic beauty: Julius Erving driving baseline in the 1980 NBA Finals, veering though the air around Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, under the backboard, and then, somehow, reaching back under the glass for a reverse layup. After the game, Magic Johnson joked that the Lakers weren't sure at the time whether to inbound the ball or ask Erving to do it again.

''Everyone who cares about basketball knows this play," Hickey writes, and it's true: Even for sports fans like myself who were merely toddlers in 1980, the words ''Dr. J" and ''reverse layup" are sufficient to summon the precise mental image.

Hickey attributes the universal joy inspired by Erving's play to the fact that it ''was at once new and fair": within the rules of the game invented in 1891 by James Naismith, and yet impossible for Naismith (or anyone else, for that matter) to have anticipated until Dr. J actually pulled it off. The relationship between fair play and aesthetic appreciation may also explain why replays of Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa's record-setting 1998 home run chase felt breathtaking just a few years ago but now seem to have lost their capacity to inspire strong feelings.

Hickey also writes of the aesthetic rewards reaped by attentive spectators who know ''what to watch for" (in basketball, according to Hickey, ''basically, everything"). As in art or music, such knowledge isn't strictly necessary but it deepens the aesthetic experience. I enjoy modern art, although I have only a layman's understanding of it. My sense of the beauty of Ray Allen's perfect jump-shooting form, on the other hand, is enhanced by the innumerable bricks I've hoisted over two decades of pickup hoops.

Our desire to better understand all the nuances of our complex games accounts for the prodigious number of retired all-stars working as sports ''analysts," as well as the countless interviews and profiles of celebrity-athletes (athletic celebrities?) that go out each day to newsstands and over the airwaves. The problem, as anyone who's watched their share of post-game interviews knows, is the incredible banality with which athletes typically talk about the extraordinary abilities and accomplishments for which they are renowned. Having run for four touchdowns or hit three home runs in a game, shouldn't there be more to say about the experience than ''It feels great" and ''I'm just happy to be here"?

David Foster Wallace devotes his essay ''How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart" (included in his latest book, ''Consider the Lobster") to the conundrum. Onetime tennis phenom Austin disheartens Wallace because he can't reconcile her on-court brilliance, not only physical but mental, with her staggeringly insipid tennis memoir. It's certainly not a lack of intelligence, as Wallace points out: ''Anyone who buys the idea that great athletes are dim should have a close look at an NFL playbook, or at a basketball coach's diagram of a 3-2 zone trap."

Wallace ultimately concludes that looking to athletes for insights into the nature of athletic beauty discounts the possibility that athletes are capable of such feats precisely because they can ''invoke for themselves a cliché as trite as 'One ball at a time' or 'Gotta concentrate here,' and mean it and then do it." Any of us in the stands or watching at home, under such circumstances and scrutiny, would buckle and fail precisely because we think too much (that, and the fact that most of us have mediocre hand-eye coordination and aren't in particularly good shape).

There's no time for distractions or doubts when Kareem is rising into your path to block your shot or when you're deciding whether to swing at a full-count slider with the opening game of the World Series on the line. It may well be, Wallace writes, ''that those who receive and act out the gift of athletic genius must, perforce, be blind and dumb about it-and not because blindness and dumbness are the price of the gift, but because they are its essence."

Of course, intellectualizing any innately emotional or physical experience (say comedy, or sex) runs the risk of diminishing, if not destroying, the pleasure we take from it. Thankfully, for the 9-year-old kid who watched as Flutie took the final snap of that B.C.-Miami game (my brother and I were lying on the floor in front of the TV; my grandmother was visiting and across the room), there was no danger of that. I'll never forget the moment: the high arc of the spiraling football, the diving catch in the end zone, and then a wave of elation, intense beyond description, on the field but also far beyond it. A thing of beauty.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home